|

|

|

Secret Love |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Montreal World Film

Festival

The Milkwoman

Minako lives alone. She delivers milk on foot in the early mornings to the households that are built cheek to jowl on the steep hillsides of her town. During the day, she works as a cashier at a local supermarket. In her own time, she reads.

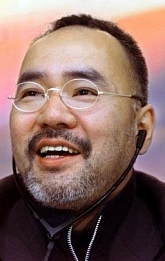

Her aunt, a writer, is one of her customers on her early morning rounds. Her aunt also takes care of her husband who was a professor of English but now suffers from severe dementia. She has been approached to write about her experiences with her ailing husband, but she remarks that she does not want to write about her own experiences, “but a story about a woman of 50 in love”. When she was still a schoolgirl, Minako resolved never to leave her city; she wanted to know its people as she and they got older; she believed that such a thing would be wonderful. She lives out this ideal, not just by remaining in her home town, but by delivering bottles of milk every morning. In an interview held at the Montreal World Film Festival, the director, Akira Ogata, talks about milk distribution in Japan and about its significance in the film.

“Since the 70s or so,” he says, “the importance of milk distribution was in constant diminution. However, in the past few years it started to be more popular because in certain towns, in towns like Nagasaki for example (where the film was shot), there is an increasing number of elderly people who can't use the steep steps to buy milk or go to the grocery store. So in the past few years this industry became more important.”

“Unlike a newspaper delivery boy,” Ogata continues, “the milkwoman distributes milk, a very nutritive element that gives life. … I asked Kenji Aoki (the scriptwriter) why he chose milk distribution rather than newspaper distribution. He says that in the case of newspaper distribution, there was only one copy given per home, regardless of the number of people living at that address. However, with milk, if there are three people living in the home, three bottles will be distributed. This is a major difference. If there is one fewer person, there will be one fewer bottle distributed. By delivering milk, we can thus understand what is going on in every home. It's a communication between the inhabitants of the village and the milkmen. It can be seen as a bilateral mode of communication in a way.” Every morning on her rounds delivering milk, Minako sees the old man who drinks his milk on the spot and from whom she immediately takes the empty bottle; sometimes she shares a few words with her aunt; and, with determination, she climbs the many steps to Takanashi Keita’s (Ittoku Kishibe) house, an old schoolmate who cares devotionally for Yoko (Akiko Nishina), his wife of nearly 27 years, who is dying of cancer.

Keita, we learn, is not merely an old schoolmate, but also an early love in Minako’s life. His father was a painter who had an adventurous romance with Minako’s mother until an accident took their lives and separated the young Minako and Keita from each other. Minako’s father also died around the same time. Keita works for The Department of Children’s Affairs (renamed as “The Department of Future Adults” - this is the scriptwriter, Kenji Aoki, poking fun at Japanese bureaucracy). There is a young boy who shoplifts in the supermarket where Minako works. The manager catches him and wants to call in the police. Minako tells him to call Keita who comes and takes the boy home. When Keita passes the supermarket window, he and Minako nod to each other with acknowledgment and respect.

At home, Keita pours the milk down the drain every day. Yoko can no longer drink it, but they have not stopped the delivery. She will not allow that. Yoko is heartened by the milkwoman’s arrival at the same time every morning. She also knows that Keita and Minako love each other. One day, Minako finds a note in the empty bottle she collects from the house; Yoko wishes to speak to her. When Yoko asks Keita about Minako, he appears indifferent. He gets up in the morning, looks after his wife, goes to work. Typically, on the way to work, he tries to compose haiku, but he is not a very good poet. The sensibility of haiku runs throughout this film. Everything is presented to us with virtually no implied comment or judgment. Keita and members of The Department of Children’s Affairs conclude, after much deliberation, to raid the house of the shoplifting boy to take him and his brother into custody. The mother barely registers what is going on. Keita screams at her so that she might understand. When he is in the privacy of his car, he weeps. When Minako catches a young colleague at the supermarket making out with the manager, she says it’s not right. The young cashier thinks Minako is a prude. Minako doesn’t care that they are not married, “just do it at home.” The old professor of English never knows what time of day it is and sleeps only in a certain chair. He is comical in his senility, but his wife’s worry is real when he disappears one day and she must search for him through the neighbourhood, up and down the narrow, hilly streets and steps. After her morning milk run, Minako rides her bicycle to work at the supermarket. Keita often sees her from the window of the tram.

At work, Keita notices an old man and asks him how old he is. “85.” He asks him how long it is between 50 and 85. “Very long.” The suggestion is clear: there is life after 50. In one scene, Minako is reading Dostoevsky and weeps as she reads of two people in love and the character who, “invented immeasurable obstacles to their union.” She is sensitive, and even sentimental. “I have someone I care about,” she writes on a postcard to a radio talk show, “but that feeling is something I can never allow to be known.” Yoko wishes for Keita and Minako to get together after she is dead. “This is what you can do for me now,” she says to Keita. “Kill the feelings in you, and you kill the feelings of those around you.” For a North American audience unaccustomed to communal observances for the dead, Yoko's funeral procession is remarkable. Her casket is carried on foot down the hillside streets, and mourners stand alongside for a great distance. It is a simple, striking scene. When Minako and Keita finally speak to each other, they are touchingly vindictive towards each other. Keita recounts an embarrassing moment years earlier, accusing Minako of having laughed at him. She scolds him for not drinking his milk. And so they are reunited.

The film does not end there, but shortly afterwards, with an enigmatic smile on Keita’s face. Minako tells her aunt, "I've never felt lonely.” Her aunt asks her what she enjoys. “Delivering milk.” One morning before making deliveries she tells her boss, "It is what gives my life meaning." This puts her love for Keita into perspective. This gentle film tells a love story, but it tells more than that. It tells the story of people. Among others we encounter in this snapshot of contemporary Japan, there is the shoplifting child and his negligent mother; the young cashier, and the manager at the supermarket; the former professor with dementia and his wife, the writer; Keita, the public official, and Yoko, his dying wife; and, of course, Minako, the milkwoman.

Contact: John Kerkhoven |

|

Note: For many years, Lois Siegel taught at John Abbott College

(Montreal). |

|

|

|

|

|

|